“We’re all Keynesians Now”, said Milton Friedman and Richard Nixon in the 60’s and 70’s respectively. In the same way now we might say, “We’re all Democrats Now”. Both statements set a standard of the common values we hold in society. Nixon meant that all economic activity was now judged through the guise of Keynesianism; it was the standard economic position of the West. The same applies now to Democracy. Whereas Keynesianism was to be our barometer of economic correctness, Democracy is now how we assess freedom. As with Keynesianism, this is a huge mistake.

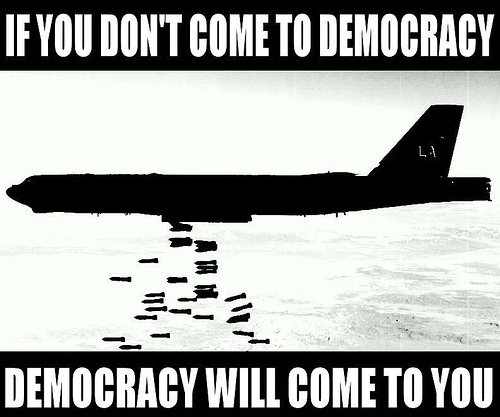

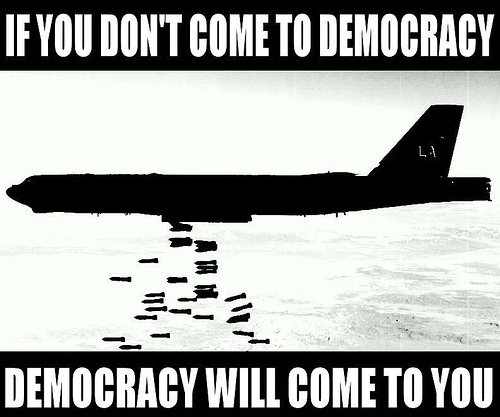

Having grown up during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, it is easy to come away with the impression that it is the duty of the West to liberate the world with this thing called democracy. There was not much discussion about what democracy actually meant, or what was so preferable about it. At times it just seemed, and still does, to be the case that the words ‘freedom’, ‘liberty’ and ‘democracy’ are thrown together in the same sentences so often that they more or less mean the same thing. As with the concepts of ‘right’ and ‘left’ that I have previously written about, it is very dangerous for words meaning important concepts to lose their meaning. By accepting democracy to mean freedom, we lose an idea of what about democracy is consistent (or not consistent) with freedom.

Libertarians have a tendency of questioning what we are told is right; we are sceptical any time we are told what to believe. As in the economic field, where we argue that the mainstream Keynesian economics should be rejected in favour of Austrian economic principles, we need to argue against the mainstream prevailing view that democracy gives us freedom. If this seems like a radical thought, it is only because for a long time as a society we have forgotten what democracy, and freedom, mean.

The most extensive work on what freedom actually means was done largely in the 16th and 17th centuries. During this time it was first theorised that there could be two forms on freedom, negative freedom on the one hand and positive freedom on the other. John Locke favoured negative freedom; he understood freedom to mean that one was free if they were not subject to force, and that human’s natural state is one of freedom. Rousseau agreed that humans were born free, but he thought that as soon a man is born he is subject to coercions of every kind, in his own words, “Man is born free, and is everywhere in chains”. Locke’s ideology led him to believe that free men could enter into agreements and contracts with his fellow man to pursue his own interests. For Rousseau however, in man’s natural state there can be no morality or law, and so due to a lack of any real security, no man is free. Thus Rousseau tries to justify the need for men to enter into a Social Contract.

As Austrian economists we should recognize Rousseau’s fundamental flaw here. In a free society, with a free market, men are forced to be moral. Capitalism is not only the world’s greatest economic benefactor of people, but also the world’s most effective social benefactor of people. Through contracts and agreements made between free men, law is created. In a free market, each man can only pursue his self-interest by enriching the people around him and providing services to them. Once we dismiss Rousseau critique of man’s natural freedom, the need for his Social Contract disappear. Nevertheless, the ideas of the Social Contract remain the prevailing thoughts behind democracy today.

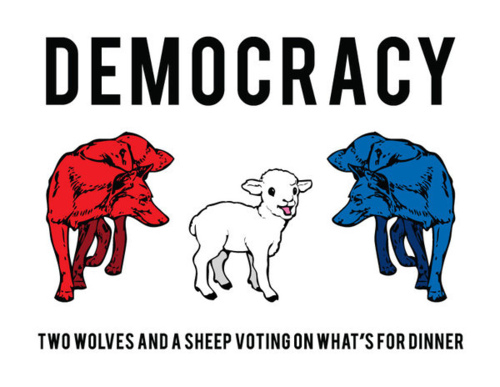

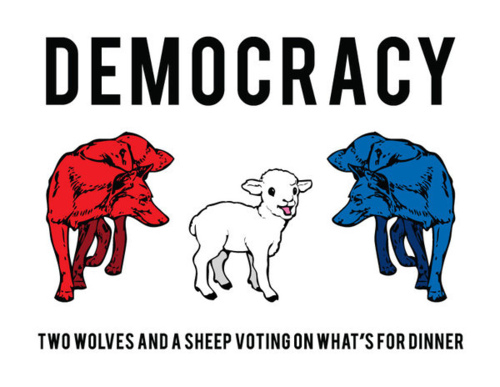

In entering into the Social Contract, into democracy, we agree to live by whatever the majority opinion of the people is. By submitting to what Rousseau calls the ‘General Will’ of the people, we are made free. Rousseau claims that only by agreeing to these conditions can we be free of the evils of self-interest. There is something glaringly obvious to me when I think about democracy and the justifications for it. For the democrat, it makes literally no difference whether the decisions made are correct or false, or even if they are in the best interest of the people or not. All that matters is that it is the opinion of the majority. It is only too easy to provide counter-examples to this claim. Can the majority vote that 2+2=5, can they vote to decide that the earth is flat, or can they vote gravity out of existence? Would you ask a footballer how to operate a nuclear plant? Would you want a dentists help to design the architecture of a school? Would you want a mentally handicapped individual in command of an army? All of the answers are obviously no. So why do we want anyone and everyone to have the power of life and death over us, the power to decide right and wrong? This raises another fundamental distinction between the philosophies of freedom and those of tyranny. We do not get our rights from the government or any majority of people, nor or right and wrong defined by them. We might think that rights and the physics of our universe come from God, or simply as a truism of our state of humanity and the state of our universe. But we must remember that no Government or any group of people have these powers.

Not only does democracy suffer from these fundamental inconsistencies with the simple truths of the universe, it fails on a practical level and results in all the things Rousseau wanted to abolish. Democracy herds people into groups; it diminishes our individuality and forces us to hide behind the dogmatism of political parties. By destroying individualism, and assigning everyone into some minority group, every man becomes a slave to every other man, because every man has the power of life and death over every other man through the majority system. Some might think that they could never be considered to belong to a minority group, but everyone does. Whether it is based on hair colour, race, personal philosophy, favourite colour, blood type or wealth, everyone can be put into a group. Once we come to recognize each other not as individuals, but as group members, divisions grow between us and before long every man has become the enemy of every man. Thus, Rousseau’s Social Contract creates the very ‘chains’ on every man he sought to abolish.