After months of massive protests against the government and subsequent crackdowns by president Viktor Yanukovych, the civil crisis in Ukraine has reached a breaking point. Last night in the majority-Russian city of Kharkiv, in eastern Ukraine, former Prime Minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko was released from prison. She has since made her way to Kiev, where she has pleaded to protesters to keep up the fight, and sworn to run for president.

“You are the heroes,” she said, addressing the protesters encamped in central Kiev. ”Heroes do not die. You have removed the cancer from this country – and for that it was important for you to stand at the barricades and face the bullets of snipers.”

“This nation will never bow to anyone – you would not allow it. A new era has begun today, an era of free people, a free country, a European country.”

However, the crisis in Ukraine is no ordinary uprising. Despite its superficial similarities to the Arab Spring, the protests in Turkey, or the student marches in Venezuela, the current crisis in Ukraine is part of a much broader struggle: a conflict within a conflict within a conflict.

Continental Divide: Russia vs the European Union

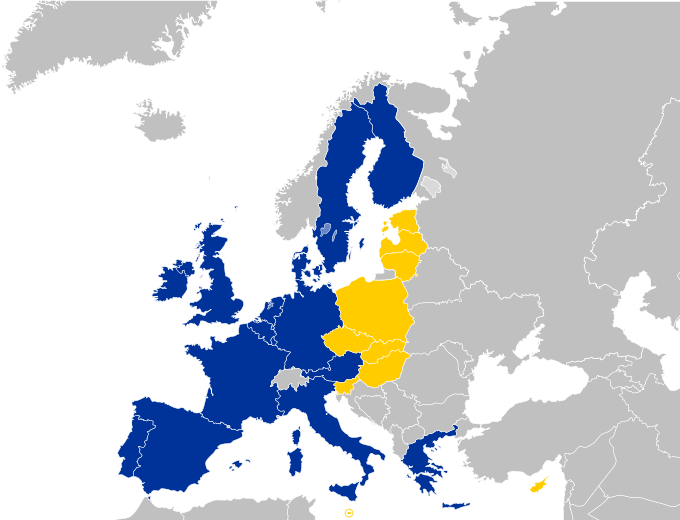

The broadest level of the conflict takes place across the entire Eurasian region. Since its inception as the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, the European Union has slowly crept eastward toward Russia, absorbing the nations of the former Soviet bloc in its wake. The most recent expansions in 2004 and 2007 brought ten countries into Europe’s sphere of influence, eight of which were formerly aligned with the Soviet Union. While the Kremlin has remained evasive about its position on the enlargement and consolidation of the European Union, two significant flashpoints have cropped up on the new frontier. The nations of Belarus and Ukraine, home to large Russian populations, have entered into negotiations with the European Commission, setting out benchmarks for reform in preparation for eventual accession to the union.

While the use of EU membership as an incentive to encourage free market reform and liberalisation in Eastern Europe has so far been a success, the governments of Belarus and Ukraine appear to be less enthusiastic. President Lukashenko of Belarus, commonly regarded as ‘Europe’s last dictator’, has famously manipulated the terms and conditions of several treaties and accession agreements in order to get the greatest economic concessions from the EU without sacrificing much of his own personal power or angering his patrons in the Kremlin. By allowing himself to be manipulated by Russian officials, particularly those associated with president Putin’s coalition, he has secured significant material and logistical support from Moscow and maintained his own hold on power.

Last November, Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych attempted to do the same, with disastrous results.

National Divide: One Country, Two Ukraines

Despite repeated campaign promises to proceed with membership negotiations with the European Union, Yanukovych refused to sign the latest accession agreement with the EU, effectively holding the treaty hostage. This sparked widespread public outrage and protests by the ethnic Ukrainians from the western half of the country, who are predominately supportive of EU membership. The eastern half of Ukraine is home to the country’s significant Russian minority, and most of the government agents involved in the crackdown in Kiev have been from these Russian regions. In fact, the last Ukrainian presidential election was decided along these geographic lines, with a majority of citizens in the Ukrainian west voting for Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, and a slightly larger majority of citizens in the Russian-speaking east voting for Viktor Yanukovych.

While the EU is in no way a libertarian paradise, accession to the union has clear advantages over continued association with the Kremlin. The European Union is essentially a free trade bloc, maintaining open borders, free capital flows, and constitutional caps on government spending and sovereign debt within its member states. Moreover, while the nations of EU do maintain some of the world’s largest welfare states, it is worth noting that the implementation of these policies has proceeded independently of the actual organs of the European Union. The reforms pushed by the European Union as an organisation have demonstrated an acceptable record of free market economics and political liberalisation.

On the other hand, Russia’s sphere of influence has scarcely improved since Soviet times. Vladimir Putin came to power after the disappointing performance of his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, who failed to bring about the smooth transition to capitalism and modernisation that was promised after the fall of the USSR. Facing the omnipresent threat of instability and chaos, president Putin has played the elite figures of Russia’s ruling classes against each other, maintaining a vast network of patrons and puppets, and creating a permanent class of oligarchs and crony capitalists in his inner circle.

Now that president Yanukovych has allied himself with Putin, could the same thing happen to Ukraine?

Political Divide: Ukrainian People, Russian State?

Unfortunately, that process is already underway. In Kiev, the ongoing standoff between civilian protesters and police is in some ways a microcosm of these broader regional dynamics. The clashes are beginning to produce large numbers of casualties, affecting civilians and police officers alike. However, the demographics of the victims reveal a striking pattern.

When the civilian and police casualties are sorted according to their respective regions of origin, a clear geographic division between the protesters and the regime begins to emerge. While some of the civilian casualties came to the protests from other parts of the country, the overwhelming majority are native to the west, which is dominated by ethnic Ukrainians. The police, on the other hand, originate primarily in the east. To those readers who have been following the coverage of the Kiev protests in both the Western and Russian media, this split should come as no surprise.

While western coverage has for the most part focused on the Winter Olympics in Sochi, the Russian propaganda machine has not been idle. Every day, RT has continued to paint a one-sided picture of the conflict. In almost every instance, the protests are described as clashes between ‘rioters’ and ‘law enforcement’, and the protesters as foreign implants. As the map above demonstrates, the reality is exactly the other way around. Ukraine is indeed being destabilised and subverted by foreign agents, and the will of the native population is in peril. But the only foreign implants in the country are the Russians.

—-

Show your support by liking The Libertarian on Facebook and following us on Twitter

![q8vEQaz[1]](../wp-content/uploads/q8vEQaz1-1024x689.png)

![00cwjai[1]](../wp-content/uploads/00cwjai1.png)